Recently, I wrote a piece for the site Appalachian History, sharing family lore. The story centered on my McGimpsey-Fullwood roots in Fonta Flora, a once-upon-a-time fertile farming community in western North Carolina disrupted by man-made Lake James.

“Like a descendant of exiles, I inherited a nostalgic yearning and inextricable ties to a time and place I will never see. Bequeathed and probably cellular too, my hand-me-down memories of Fonta Flora are treasures.”

Excerpt from Fonta Flora: Blue Ridge Atlantis

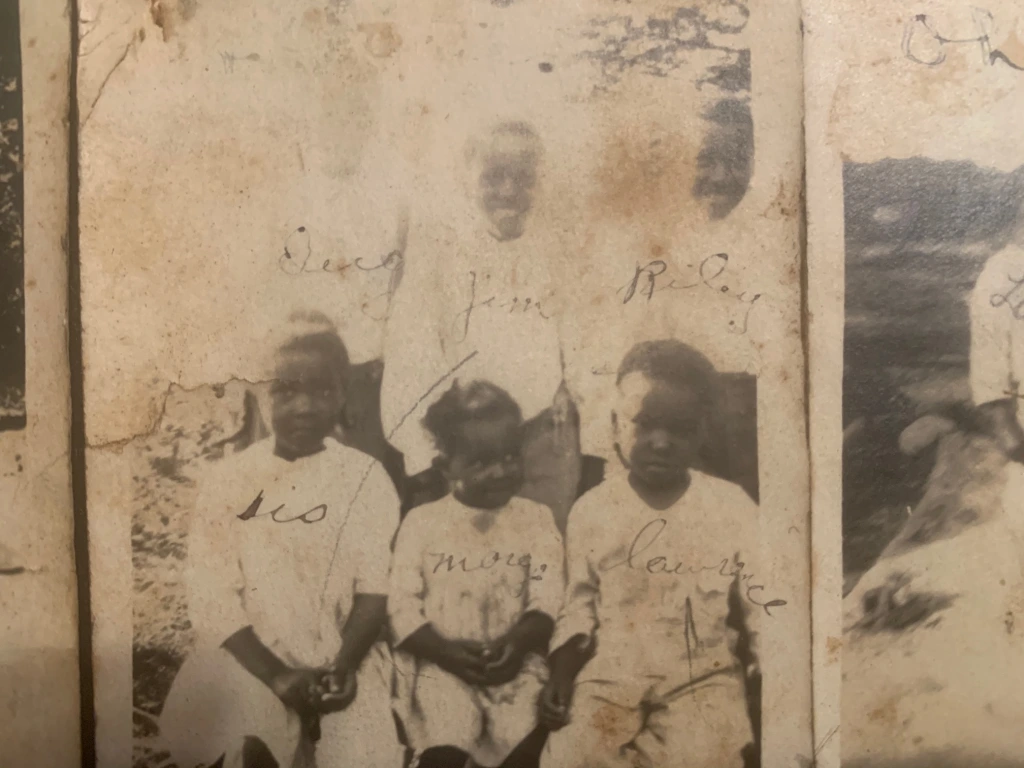

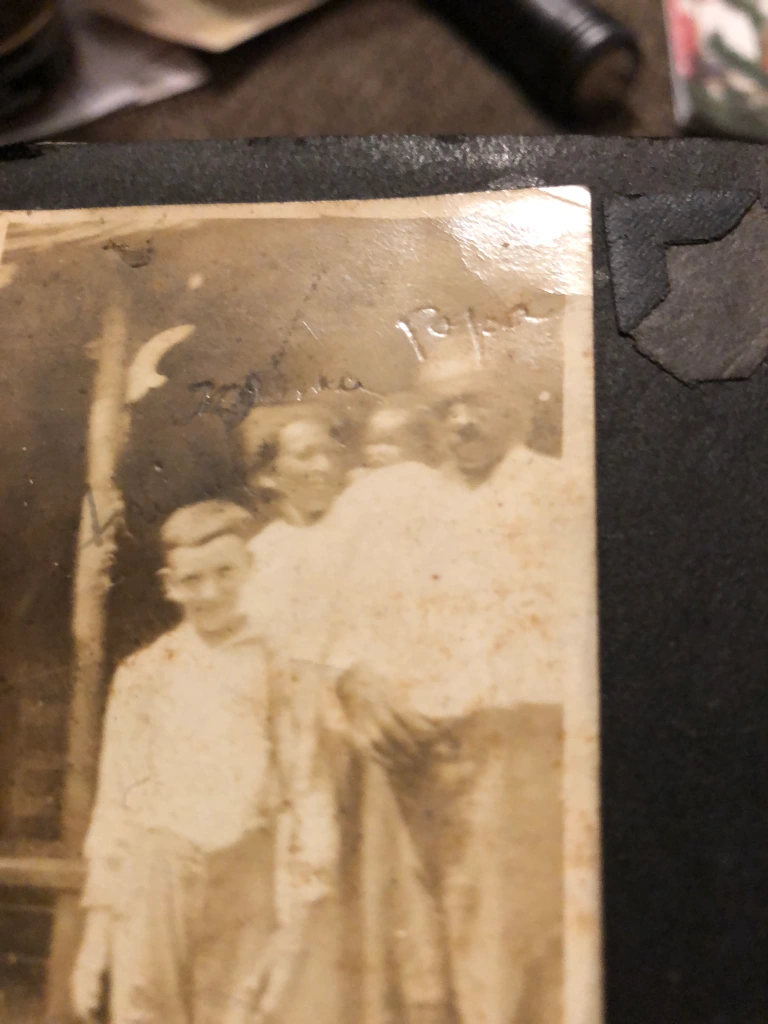

While the site’s editor chose a different title, my working title for the story was Provenance. Defined as “the place of origin or earliest known history of something,” the word provenance epitomizes Fonta Flora to me. Documents going back as far as the early 1800s show Fonta Flora (at one time also known as Linville) was once home to virtually all my paternal forebears. Having stories, photos and visceral bonds that allow me the privilege of knowing my grandmother’s grandmother’s mother and more kin is a privilege I do not take lightly.

The “fonta” in Fonta Flora translates from Latin as “source” or “origin”. Thus, my provenance, my source is the source of the flowers and also the flowering for the McGimpsey-Fullwood family.